Harnessing Her Superpower: Palestinian Philadelphian Jude Husein Fights for the City and State

Lauren Abunassar

Jude Husein finds it difficult to stay still. Then again, for most of her life she’s been moving quickly.

Jude Husein serves as Chief of State Advocacy and Strategic Initiatives at the Pennsylvania State Senate.

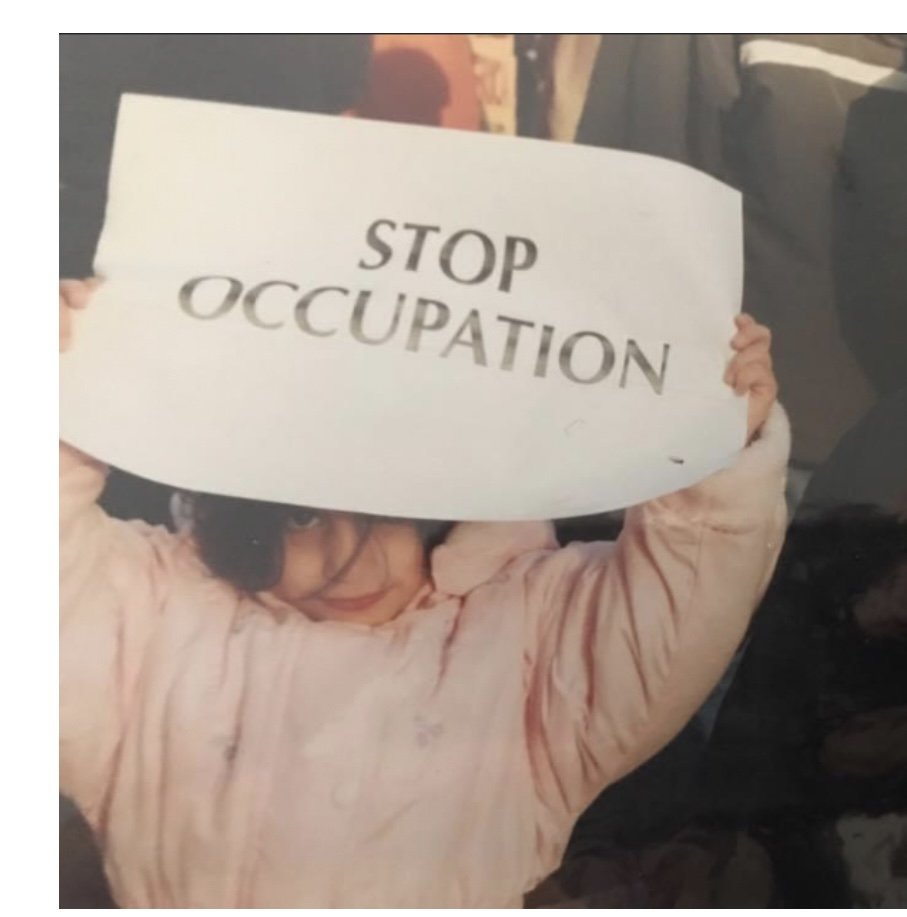

At just four years old Jude Husein was already out in the Philadelphia streets protesting. Photo courtesy of Jude Husein.

Born in Ramallah, Palestine she immigrated to Philadelphia when she was four and quickly found herself following her mother — a passionate community advocate — to community, police, and zoning meetings all over North Philadelphia. As she got older, Husein would travel two and a half hours every day to get to school, walking 12 blocks from her house to the L. Her first experience as a community advocate was fighting for structural changes in her high school after it experienced a wave of violence and leadership turmoil; eventually, she was asked to serve on the search panel for a new principal for the school. She was 16 at the time.

And today, the 26-year-old serves as Chief of State Advocacy and Strategic Initiatives at the Pennsylvania State Senate. She was named 2024 Activist of the Year by The Philadelphia Citizen, a 2023 Philadelphia Forty Under 40 by City & State PA, and in 2021, she spearheaded efforts for Philadelphia to celebrate its own International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People. “I always told myself, if I had community, I could do absolutely anything,” Husein said.

Above, Husein is pictured at the first annual Philadelphia Palestine Day in 2021. Photo courtesy of Jude Husein.

She had a chance to celebrate Palestinian community this past December, during Philly’s fourth annual Palestinian solidarity day. Though the event debuted in 2021, Husein has encountered roadblocks for hosting it ever since October 7th. Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle Parker even revoked approval for the 2024 event. Husein persevered, however, and even went as far as hiring an airplane to fly the Palestinian flag over the city on the day community members were finally allowed to celebrate. The flagpole is too short, she remembered thinking. The plane seemed like a good option.

“I think people tend to say things like, ‘you’re a dreamer, you’re idealistic. You’ve really romanticized the notion of peace,’” Husein said. “But I truly believe in this mindset of the billionaires will be the billionaires, but the people are the people. And there’s more of us than there are of them… I believe when government doesn’t work for the people, the people work for the people.”

In her role at the Senate, Husein straddles that boundary between working for government and the people. Husein admitted she’s always aware of the fact that she is usually one of the only, if not the only, Arab that some people will ever meet in their life. The sense of responsibility that accompanies this understanding is keenly felt. She is both a steward of her own history and the history of her ancestors.

My family has a history of always going back to Palestine,” Husein said. “In moments of exile, they made sure to always return to home.” The rarity of this, the blessing of being able to go back, is not lost on her. In the ‘60s, her grandmother took Husein’s father and his siblings to Jordan following a mass raid by Israel. They returned to Palestine a few months later, her grandmother adamant on returning home. Though her father eventually immigrated to America, Husein remembers him always encouraging his children to get to know Arabic language andculture. Husein herself, the youngest of four, was the only one of her siblings to be born in Palestine. And even after moving to Philadelphia, she remembers return visits to her homeland as frequent and punctuated by small moments of magic. “Once, [while visiting Nablus, Palestine while my mother taught English] we stayed in an apartment above a bakery for three months,” Husein said. “And at the end of the night, the bakery would give us all of the sweets left over from the day. It goes to show Palestinian hospitality at its finest: you’re always fed all the time.”

These celebrations of history, identity, and culture are something Husein treasures. “I stand on the shoulders of giants,” she said when describing her now 112-year-old grandmother, who resides in Palestine.

Jude Husein is pictured above with her grandmother in 2023 in the Palestinian village of Ein Yabrud, just outside of Ramallah. Photo courtesy of Jude Husein.

Husein began to recognize a different understanding of Arab identity growing up in America. “Growing up, it wasn’t necessarily being Palestinian that was an issue, it was being Arab. And with the last name Husein, I was really bullied,” she said. “People would always refer to me as Saddam Hussein. Or they would ask: ‘Are you Saddam Hussein’s sister,” or “how are you related to him.’”

As recently as just eight months ago, a colleague jokingly asked her if she knew Saddam Hussein.

“I call those moments my alien moments,” Hussein said. “[Moments where] I really knew I wasn’t the same as some of these people. I just don’t see things that way… There’s always that one person out of ten that is the problem and then everyone is super motivated by fear. Because nobody wants to be different. Nobody wants to be the alien. No one wants to say ‘that’s wrong.’ I think [that is] where the disconnect in humanity is: where we just stop listening. Because we think we’re so far away from one another and that’s just not true.”

Husein finds hope in grassroots community leaders and the youth community. In addition to her role at the Senate, she has been working as the Deputy Executive Director of BOLT, a Philadelphia nonprofit dedicated to empowering BIPOC leaders. She also keeps busy as a board member of PHILADELPHIA250, a nonprofit fighting for community-led change in Philadelphia. In other words: she’s doing work all over the city, intent on harnessing what she calls her superpower: her love for people. She laughs this off, admitting, “I think my dad still doesn’t know what I do for a living.”

But the work, for her, is also a way of offsetting the real grief and defeat ushered in by the ongoing genocide in Gaza, the ominous shade cast by the second Trump presidency, the urgent needs and disparities in Philadelphia. “Defeat is part of [my] untold job description,” Husein said. “When I have to explain how humanity matters to my colleagues – on a variety of different issues, not just related to Palestinians — I am very defeated. But it’s not a defeat that paralyzes me. It’s why I can’t be still.”

Her unchecked belief in the power of community-led change is a counterweight to these moments of defeat. It’s also a testament to the resilience she credits directly to her Palestinian identity, an identity that is as informed by grief and loss as it is by a history of overcoming. For Husein, she sees Palestine in Philadelphia — in the youth activists, in the older generations sitting outside on stoops, in the storytelling, in the neighbors she can both count on and speak for.

Reflecting on this, she corrected herself: “There is a difference between grief and defeat,” Husein said. And she does grieve. But she shows up for work because of the people that count on her, remembering another Palestinian ideal and converting it into a metaphor for community advocacy work: You don’t eat until everyone else has eaten.

“If we look at history, we protect our people at all costs,” Husein said. “We haven’t hit rock bottom until we turn our backs on one another.”

***

Lauren Abunassar is a Palestinian American writer and journalist. A Media Fellow at Al-Bustan News, she holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and an MA in journalism from NYU. Her first book Coriolis was published as winner of the 2023 Etel Adnan Poetry Prize.